|

|

Nathan

Percy Graham – 'Percy'

|

|

| |

by

Benjamin Ifor Evans, 1920

|

|

NATHAN

PERCY GRAHAM was born in London on August 30th, 1895.

He entered the Classical side of the City of London

School in 1907, and remained there 'til the summer

of 1914. It was characteristic of his versatility

that he obtained first the Sir William Tite Scholarship

in Classics, which he declined, and then the John

Travers Scholarship in Science with which he proceeded

in October 1914 to University College, London, and

where he joined the Faculty of Engineering.

NATHAN

PERCY GRAHAM was born in London on August 30th, 1895.

He entered the Classical side of the City of London

School in 1907, and remained there 'til the summer

of 1914. It was characteristic of his versatility

that he obtained first the Sir William Tite Scholarship

in Classics, which he declined, and then the John

Travers Scholarship in Science with which he proceeded

in October 1914 to University College, London, and

where he joined the Faculty of Engineering.

Early

in 1915 he joined the Officers' Training Corps, and

later in the year obtained a commission in the Royal

Garrison Artillery. He went to France with his battery

in August 1916 and was present at the Battle of Ypres,

Passchendaele and Messines. At this last place he

sustained shell-shock and went into hospital at St.

Omer. He was later removed to the Denmark Hill Hospital

and after two months' convalescence at Craiglockhart,

near Edinburgh, was invalided out of the army in December

1917. But he never recovered – his health had

been permanently undermined.

Graham

left the army a changed man, his whole mental and

spiritual outlook completely transformed by the experiences

through which he had passed.

In March

1918 he re-entered the Engineering Faculty at University

College and immediately threw himself with all his

energy into the work of reorganising the student life.

Within

a few weeks he was elected Editor of the Union Magazine

and brought to that journal at once more seriousness

and more wit. His own contributions were a solid background

to the literary matter he so successfully introduced.

The poem Piccadilly Circus illustrates adequately

the tone and thought he maintained, while a more ephemeral

revue of topical matters, Hullo Ukrainia, buries

with its lost illusions a large amount of too transient

humour. His success as an Editor induced his fellow

students to elect him President of the Dramatic society.

The result was a production of Prunella, executed

with taste and vigour. He was now among the best-known

figures in the life of the college and when the Union

Society, a mere wraith of its pre-war solidity, sought

again a student President it was to Graham that it

turned. He organised again with quietness and tact,

and built up once more those pleasant undergraguate

groups which had meant so much to students in the

sunny pre-war days. He became Treasurer too of a newly-formed

Socialist Society. He was attracted to this movement

more as an idealist than as a politician – more

by the Republic of Plato than by Das Kapital

of Marx. He became interested too in local politics

and was elected Propaganda Secretary of the Stoke

Newington Labour Party. He followed Socialism and

Labour, together with so many of his young contemporaries,

not as a creed or a party, but because it seemed that

the Vision of Truth had led him here, though not to

rest.

Percy (sitting right)

and engineering colleagues c.1914 or 1918-20

Graham

did not allow his political and other activities to

interfere with his reading. He was not only familiar

with the chief English and Classical authors, but

his amazing energy made it possible for him to read

widely in modern French, German, Italian and Spanish,

whilst the catholicity of his taste is sufficiently

illustrated by the fact that at the time of his death

he had made some progress in both ancient Egyptian

and modern Welsh! It was during his college career

too that he wrote most of his shorter poems.

In the

meantime, in June 1919, he had obtained an Honours

B.Sc. Degree in Engineering and after a few months'

private study he passed the intermediate Examination

in the Faculty of Arts.

In April

1920 he took up a post as engineer in Bolton, Lancashire.

He found the work and the atmosphere uncongenial and

he formed the intention of abandoning engineering,

for which he had never cared, and of settling in some

quiet cathedral city where he could devote himself

entirely to literature. But death overtook him before

he could carry it into effect. He succumbed to an

attack of heart failure on June 20th, 1920.

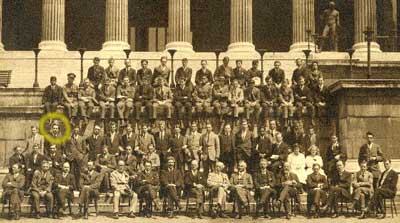

Percy (circled) and colleagues at University College,

London, c.1914 or 1918-20

(Click photo to enlarge)

Graham

was among that heroic generation which went into the

war because it believed that the principle of Freedom

was at stake. He lived long enough to realise that

the simple faith which inspired men in 1914 was never

to be realised. The sight of youth's sacrifice becoming

but a counter of the political game stirred in him

a strain of iconoclasm foreign to his real nature.

"After

all," he wrote, "the Latin trado

means I betray as often as it means I hand

down." Passionately he dedicated himself

to the cause of Youth, for Youth alone could regenarate

the world.

He found

a newer, harder faith in no recognised creed, nor

in any established church. During the last few months

before his death he worked at a long poem, Phaethon.

His belief and thought are seen there remodelling

themselves, through sorrow and passion and the heavy

experience of many things, into an organic, a creative

faith that Truth must be discovered by each man in

the travail of his own soul.

"No

man's religion," he wrote, "can be complete

'till he dies." "The duty of a father or a teacher is

not to pump in creeds or faiths but to plough and

fertilise the soil in which growing consciousness

can sow its own seeds." It was not a belief in

any materialist conception of history, but a desire

to make man free for spiritual progress that made

Graham a Socialist. He desired to emancipate men from

the economic servitudes which prevented them from

giving full play to their creative energies; he desired

to break down the barriers which stood between men

and their vision.

In Phæthon

he has reached a vision of life not unlike that of

Shelley in his Italian period. He is still sensitive

to the cruelty and pain which wreaths Life in its

embrace, but he sees standing out magnificently clear

some one, unchangeable purpose. He writes:

| |

Oh

God, or poesy, or great ideals

Oh, they are one – this mighty trinity.

One bond of life above three diverse seals,

One stream through different springs!

|

|

And if

it should be false – the God, the poesy and the

ideals, the fear sweeps over him for a moment –

life would still be worthwhile, the dream would in

itself suffice:-

| |

Dream

on – and thou, Dream

on – and thou,

Thou meek handmaiden pale and timorous,

Poor Poesy! dear Poesy! Tho' brief

My feeble flight, tho' week my wings unfurled

Across the rainbow sky, tho' death await

And darkness be my meed, oh aid me now. |

|

He felt,

as did Shelley, that men were following the transitory,

worthless things, and that the Spirit of Life was

left solitary and neglected:-

| |

If

but the music of the songs I sing,

If but the fragrance of the flowers I wind

Into a heavenly coronal, can bring

The vision of my God, so long a wraith

Unseen by tributary minds.

|

|

He closes

his envoi to Phæthon with a recapitulation

of his poetic faith:-

| |

If

but the dreams I dream, and thro' the skies

Send earthwards, clothed in majesty of song

Unwound from the magic weaving of thy lute

Oh Poesy, should wake a chord along

The world's wide resonance, that hearts now

mute

May seize some wandering tremor from its sound

And organ-like, give back an answering note

If but in stagnant souls and visions bound

With bonds accursèd

and with vows immote

To one fixed image, graven of spiritual stone

Some wandering thread of song at last should

seek

And with a godlike instinct find the throne

Of God who is within.

|

|

Phæthon

is an intensely subjective poem, as unintelligible

in itself as Shelley's Alastor, yet although

he speaks here of himself and his beliefs, the portrait

is not complete. Phæthon, a serious philosophic

poem, gave no scope for that gentle sense of humour

which lightened his thought and made his company so

evenly pleasant to his friends. He delighted in words

themselves, to trick and play with them, and some

of his puns would have made even an Elizabethan blush.

It is thus perhaps that he should be remembered, sad

with much that he has seen, strong in faith which

demands Life and not Rest, quiet as in thought, but

with his whole being ready to catch every glance of

a smile. He saw the Ideal and dedicated to it a splendid

loyalty, and in its service his ardent spirit flamed

itself away.

B.I.E

~1920~

|

|

Nathan

Percy Graham – 'Percy'

|

|

| |

by

Benjamin Ifor Evans, 1920

|

|